« The cause of the people is the cause of the nation, and the cause of the nation shall be the cause of the people » – Lenin

If there are available now in France a number of satisfying works of reference which allow us to understand German national-bolshevism well, this is absolutely not the case for Russian national-bolshevism, the existence of which we are just now discovering. Thus the work of Mikhail Agursky, though hostile, is a source of great first importance of information and reasons to meditate, even to hope.

The thesis of the author, inspired by the reflections of Ortega y Gasset in The Revolt of the Masses, is that the marxist and socialist components of Russian bolshevism are only « historical camouflages » for a really geopolitically and historically more profound process. For Agursky, Lenin practised a double language, orthodox marxist in his writings, which should only be considered as works of « public relations », he placed himself in fact in the line of Alexandr Herzen who rejected the West and who promoted an invasion of Western Europe by the Slavs. Since the beginning of the century, Lenin and the bolsheviks would have assigned the goal to themselves of giving the leadership of the world revolution to Russia and the Russians. In this view, national-bolshevism would be the Russian nationalist ideology that would make the Soviet political system legitimate from the nationalist point of view and not from the Marxist point of view. National bolshevism would thus make an attempt for world domination of a Russian Empire cemented by communist ideology.

Examining a period which extends from 1870 to November 1927 (date of the triumph of Stalin in the 15th congress of the Communist Party), Agursky’s book covers successively different facets of Russian national bolshevism:the contribution to it by non-Marxist revolutionary parties, its relations with the proto-fascists of the Union of the Russian People, the ultra-bolshevik faction « Forward 1 », the futurist influence, the importance of Jewish intellectuals in national-bolshevism, and Smenovexism.

The Non-Marxist Heritage of the National-Bolsheviks

Agusky sees in Russian national-bolshevism the result of a certain number of non-Marxist influences.

This of Aleksandr Herzen which figures that Russian socialism would benefit from pan-Slavism and that Russia was a young nation, in better health than the West, whose future was to create an Empire « which would contain the Rhine, would go to the Bosphore and on the other side would extend up to the Pacific ».This of Mikhail Bakunin, anarchist with a nationalist basis who made himself the supporter of Nikolai Muraviev-Amursky, governor of Siberia who conquered a part of the territories of the Far East with the agreement of the government, and who figured that the Slavs should have a national interest in revolution. This of the Prussian, Ferdinand Lassalle, whose socialism mixed with a very strong nationalism and a statism no less strong. This of the populists, principally after the revolution when numerous members of the Revolutionary Socialist Party join the bolsheviks, as the SR were traditionally opposed to the capitalist West and, messianists, believed that the Russian people would create its own form of socialism which would be the avant-garde of all humanity.

Red Flags and Black Hundreds

The Union of the Russian People, known also under the names of Black Hundreds, represents a form of Russian proto-fascism. A pro-German, anti-English, and anti-Yankee movement fearing the expansion of the yellow peoples, it condemned with force capitalism, parliamentarism, and liberalism, and envisaged a violent anti-Romanov revolution. Its militant base was formed in the most part by industrial workers. Contrary to current opinion, this group was not in violent opposition with the Russian communists but in concurrence and a certain admiration existed on its part for them, driving them to timely alliances and creating passages of militants from one camp to the other.

Plexanov estimated that the URP’s (SRN po-russki) ranks were 80% made up of proletarians and that they « would become ardent participants of the revolutionary movement », Peter Struve affirmed that the URP was a revolutionary socialist party, at the congress of the Social Democratic Party of 1907, Pokrovsky that one will find in the extremist Bolshevik fraction « Forward 1 » insisted on the positive sides of the URP. Lenin was firstly reticent on these positions, and then was convinced of their good foundation by Maksim Gorky who had been in correspondence with the Black Hundreds since 1905.

On the side of the URP, this led to numerous changes in strategy for the future communists in order to bring the downfall of the liberals. For one of the leaders of the Black Hundreds, Apollon Maikov, they « pursued the same objectives as the revolutionaries, that is to say the betterment of the conditions of life, a goal which coincides in a certain way with the teaching of the social anarchists . . . The consitutionalists call the armed revolutionaries ‘left-wing revolutionaries’, and the Black Hundreds ‘right-wing revolutionaries’. From their point of view this definition has a certain legitimacy . .. Because we all think that the consititutional form of government brings the total domination of capital, and in such conditions when power will be exclusively in the hands of the capitalists, who will only hold it for their own advantage in order to oppress and exploit the population. » Another leader of the URP, Viktor Sokolov accused the ruling bureaucracy of wishing to incite its members « to struggle against the revolutionary elements, and thus to weaken the two parties by this struggle ».

Starting in march 1917, most of the 3,000 members of the URP (at the same time the bolsheviks were only 10,000), started either to join the Bolshevik Party or to work for it after the Revolution. Thus one sees the journals of the Black Hundreds calling for the dictatorship of the proletariat, the head of the URP students in Kiev, Yuri Piatakov, becoming one of the heads of the Bolshevik extreme-left, some less known militants becoming responsible for Soviets or working in the Cheka (later-KGB), while numerous others became important membres of the Orthodox Church loyal to the regime (the head of the URP of Tiflis became also the Metropolitan Varfolomei and died of natural causes, at 90 years of age, in 1956).

The Faction « Forward ! »

An internal and then external faction of the Bolshvik Party, finally reintegrated within it, « Forward! » grouped together the semi-totality of Bolsheivk intellectuals (Maksim Gorky was one of its warmest partisans) and exercised an astounding influence on Soviet society under Lenin and after his death.

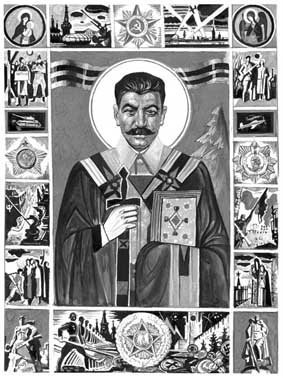

Most of the leaders of « Forward! » prospered under Stalin and not one of them had to suffer from the purges. One can consider them as the theoreticians of the national and totalitarian turn of Bolshevism. If a lot of their ideas are very interesting in themselves and would merit long developments (the Faustian concept of life, belief in the creation of an over-humanity, totalitarian democracy valuing the group and negating individuality) they concern us principally because they have contributed largely to the development of Russian national-bolshevism firstly by the deification of the Russian people which gave birth to a semi-religious movmement « The Constructors of Gods », followed by an absolute rejection of the West. On this point they affirm that Russia was (after the revolution) a colony of the West, that their revolutionary tradition was purely Russian, and that the Revolution of 1917 had a national element. Finally it was the members of « Forward! » who were at the origin of the Proletcult (proletarian culture) affirming that the people is the only creator of the culture and that deviant individualities must be eliminated.

The Nationalism of the Futurists

The Russian futurists range in their totality in the camp of Soviet intellectuals to which they brought a solid nationalism developed since their appearance well before the war. Insisting on the purity of the language, they proposed the exclusion of terms of foreign origin from the Russian vocabulary. Favoured intellectuals, they travel therefore « to the West » from which they mostly left reactions citing its decadence and its weakness opposed to the youth and force of the Russian East, affirming that « The light of the East is not only a liberation for the workers. The light of the East is a new attitude for man, woman, and things », or writing, « I moo like a bull, being lucky that my motherland – my mother – is the Russian land, the Russian land, the Russian land! I am ready to live my life anew, by only knowing the words ‘Russian land’. I do not know a more profound bliss than to be Russian. I do not know sensations deeper than being Russian, a true Russian. »

A Jewish National-Bolshevism

One of the most surprising points of Russian national-bolshevism of the 20s is the importance in its ranks of intellectuals of Jewish origin having for the most part crossed a mystical phase. For these ones, revolution meant at the time a messianism and permitted them to affirm their love of the Russian fatherland without being rejected by anti-semitism in Russian society.

These Jewish intellectuals organised either in emigration in which they participated in the Smenovexist current, or in Russia itself, where, despite their heterodoxy, certain ones of them occupied important positions. If Ilya Ehrenburg, known throughout for his articles and ultranationalist radio broadcasts after 1941, did not have extraordinary conceptional originality, one cannot say the same for two of the principal Jewish theorists of national-bolshevism: Isai Lezhnev and Vladimir Tan-Bogoraz.

The first, even though opposed to the communists during the Revolution of 1917, was one of the favourites of Stalin, responsible for the literary pages of Pravda and one of the principal literary critics of the Soviet Union. Influenced by Nietzsche, Shestov, and Hegel, he rejected traditional values, law, and ideology, and only recognised as criteria « the spirit of the Russian people », believing that this carried an imperial dimension: « Russian imperialism (from ocean to ocean), Russian messianism, Russian Bolshevism (at the global level) are all going in the same direction ».

Vladimir Tan-Bogoraz, coming from the most radical wing of the populist movement, became the director of the Institute of Religions. Violently anti-Christian, he showed a certain preference for Islam, seeing in the God of the Old Testament a populist-terrorist and his writings resent the influence of the cabal. Affirming himself proud of being accused of national-bolshevism, he saw in the reign of Peter the Great an example for the new regime and demonstrated a very strong anti-Westernism.

Smenovexism, A National-Bolshevism in Emigration

But the purest and most interesting national-bolshevism was born in the ranks of the White emigration. In October 1920, Nikolai Ustrialov made reference to the German national-bolshevism and confided in his friends his decision to preach a Russian version of it.

Teaching at the University of Moscow, Ustrialov became known in 1916 for collaborating with the periodical > (« Problems of Great Russia ») and by defending in it Russian expansionism and a strong State. The same year he gave conferences on the slavophiles, where he affirmed that Russia had a global mission. An active member of the Kadet Party, he witnessed with satisfaction the fall of Tsarism and collaborated in the daily > (« Morning of Russia ») where he affirmed that the Bolshevik Revolution was really authentically Russian, just as he criticised the orientation of the exterior politics of the Bolsheviks. In the summer of 1918, he had to flee from Moscow and joined the zone held by the armed Whites. A refugee sometimes in Omsk, he ended up emigrating to China in Harbin, whence he criticised the counter-revolutionary forces linked too closely for him to foreign interests . . . In November 1920, Ustrialov, with three exiled poets who will later become celebrated Soviet writers, founded the magazine > (« Window »). His influence was immediately very great in the emigration, some national-bolshevik conferences were held in Paris, a Smena Vex bulletin appeared in Prague, a daily « Nakanun » (« On the eve of ») was published in Berlin and an important militant group appeared in Bulgaria (its head was later assassinated by the Whites). In Russia even, smenovexism did not pass unnoticed, Lenin envisioned a triumphal return of Ustrialov to Moscow (in fact that did not happen but most of his partisans returned to Russia), had some Smena Vex articles published in Pravda, financed Nakanun secretly, and evoked favourably the existence of this current during the 11th Congress of the Communist Party in March 1922. After the death of Lenin, the Smenovexists who sustained the attacks of Kamenev, Buxarin, and Trotsky, were defended by Stalin personally as one said that he appreciated them a lot. It is said that during his expulsion from the USSR, Trotsky cried out, « It’s the victory of Ustrialov! »

From a theoretical point of view, Ustrialov who thought in terms of the measure of power, affirmed that « Only a State physically powerful can possess a great culture. The small powers can, by nature, prove their elegance, honour, even heroism, but they are organically incapable of grandeur; that requires a grand style, a protection in the great unity of thought and action ». He considered also that: « The Soviet government will force by all its means the reunification of the peripheral territories with the Centre, in the name of the World Revolution. The Russian patriots will struggle in order to attain the same objective in the name of an indivisible Great Russia. Despite all the ideological differences, they all follow practically the same path. »

While one of his disciples, the poet Vladimir Xolodkovsky, cried, « The USSR is not only a state of the development of Russia as an ethno-geographic entity, it is a turning point in the evolution of nationality in humanity. If the Moscow of Kalita was able to bring together the Russian land into a great empire by glory and oppression, Soviet Moscow has started to bring together the land into an Empire of the workers and of liberty ».

Russian National-Bolshevism Since 1927

Despite its 500 pages, the work of Agursky leaves us in a certain sense of lacking. It fails to provide us with an analysis of triumphant stalinism, of the « Great Patriotic War », even of the evolution of the opinion of the emigration.

At the same time, the current or contemporary situation remains to be explored.

Which ideological genealogy can one trace to the national-bolshevik dissidents at the beginning of the 1970s? Whether these be the members of the Fetisov group (in the name of A.A. Fetisov who quit the CP in order to protest against destalinisation) affirmant that « leninism has incomparably more in common with Russian Orthodoxy and Slavophilism than with Marxism and Catholicism » and that « only a union of Orthodox Russia with Leninism can produce this view of the ideal world for the Russian people which will create a synthesis of the entire experience of the people through the centuries ». Or whether it be a question of the « ultras » of Gennadiy Shimanov, paritsans of the Third Rome who figured that the Soviet regime was the only political organisation which was able to oppose « the Western democratic rot » and to mobilise the people towards a new historical goal: Empire.

Whether it be also, finally the national-bolshevik affiliation of the leaders of the current All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, the Russian Communist Party, or the Communist Party of the Russian Workers and some political groups and journals classed in the « red-brown » circle.

Christian Bouchet

(translated from the French by Thomas Smitherman)